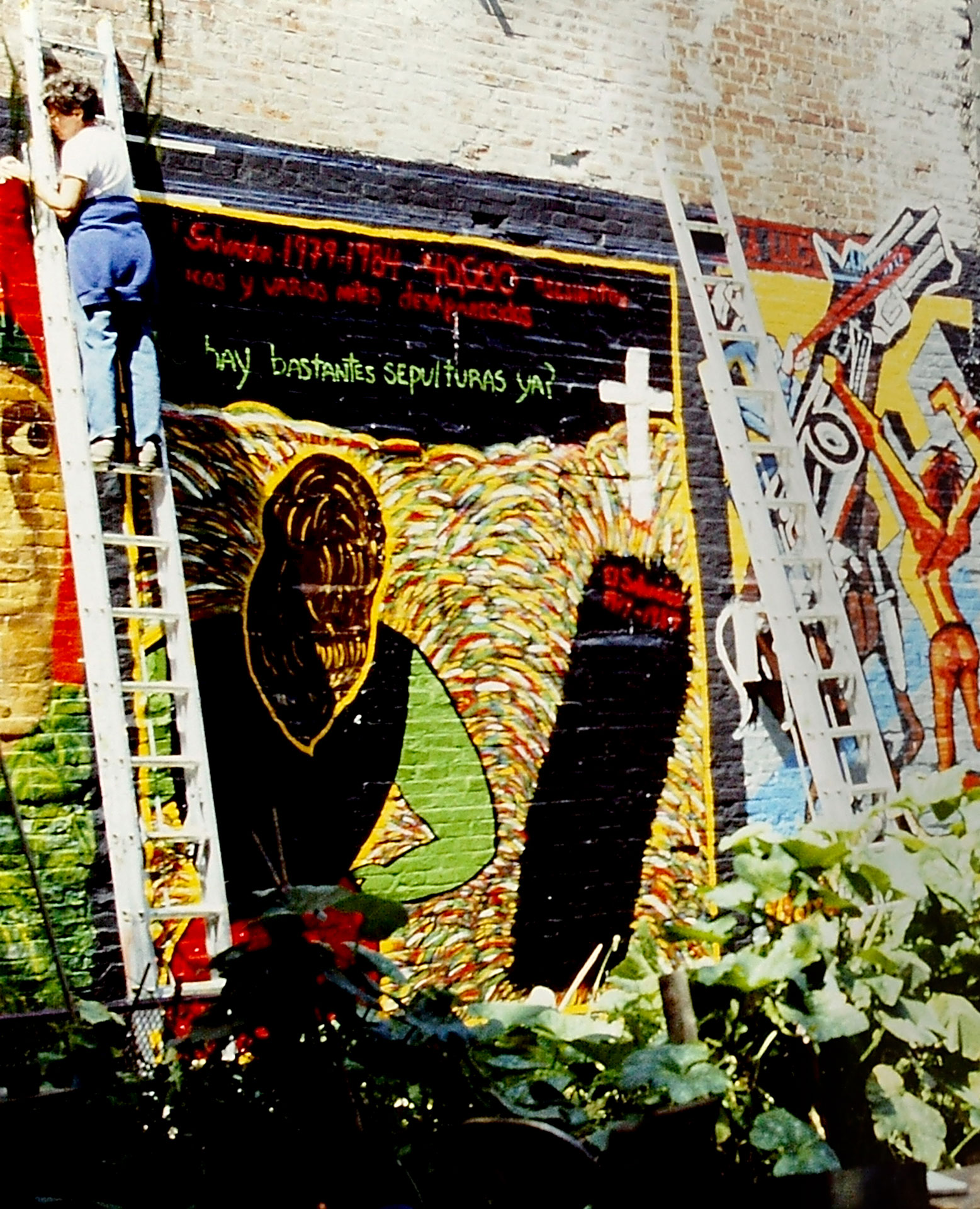

10. The Disappeared

PAT BRAZILL

1985, 14’ x 14’

Photo © Pat Brazill

It was the article “Women’s Grief Gives Rise to Activism in El Salvador” in The New York Times (February 2, 1985) that, according to Pat, was “so completely heartbreaking and depressing that I knew, while ruminating on my mural, what it would portray.”

In The Disappeared, Pat acknowledges all the mothers who waited for their missing sons to come home, holding out hope for hours or days before accepting that they were probably dead. The grieving mothers are represented by a lone woman; she faces a landscape marred by an open grave, “essentially a black pit.” Above are the words ¿No hay bastantes sepulturas ya? that translate “Aren’t there already enough graves?” Above them is the estimated number of political assassinations and “disappeared” people in El Salvador between 1979 and 1984. Its civil war (1980-92) left at least 75,000 people dead.

In 1985, Pat was a photographer who had begun to explore painting. Acting on the opportunity to move to New York and sublet an inexpensive apartment uptown, she learned about La Lucha from a friend who encouraged her to apply. “It seemed like a wonderful opportunity to participate in a big project—not only in scale, but also as a way to improve the community, address political issues, and work in a new, very different way. I remember, after an initial wariness on both sides, the friendliness of people in the neighborhood. My Spanish improved, as did my street smarts.

“What I most remember is that confident, lively group. Many of the artists were handsome and beautiful, and many were exceptional artists. While I didn’t leave the project feeling like mural making was the perfect art form for me, I’m eternally grateful for that opportunity. I loved being part of it. It forced me to step outside of my comfort zone, to be more social, more in the world. What’s the point of being in New York if you’re not out there in the thick of it?”

Pat would paint after work, all her supplies in a green garbage bag stuffed into a shopping cart. “Getting it up and down subway stairs was hell. Eventually people began to recognize me and often helped—particularly downtown. Covered in paint and grubby at the end of the day, I must have presented an aura of being homeless rather that of an artist. People leaving the train would drop money and food into my lap, not making eye contact, but making contact all the same. I tried to refuse, but eventually I took what was offered to me, especially a seat, and felt cared for in an odd (and sometimes humorous) way. To keep the spirit of giving going, I brought peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to hand out as needed. There were many homeless people, and what I brought didn’t go far, but it was something.”

After working in publishing (Rolling Stone) and as a prosthetics technician (making artificial legs), Pat established her own business—working as a mailler and making chain maille jewelry. Linking rings together, she aims to harness the power of repeating patterns, celebrating the beauty of designs from the distant past. patbrazill.com